-40%

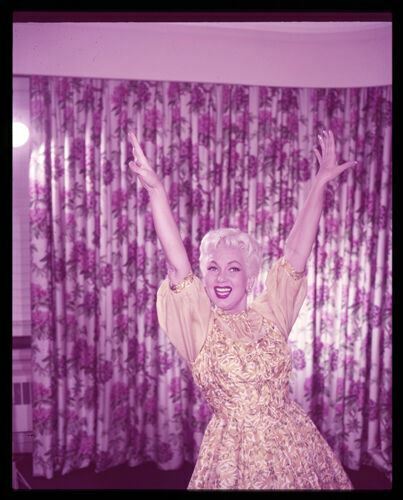

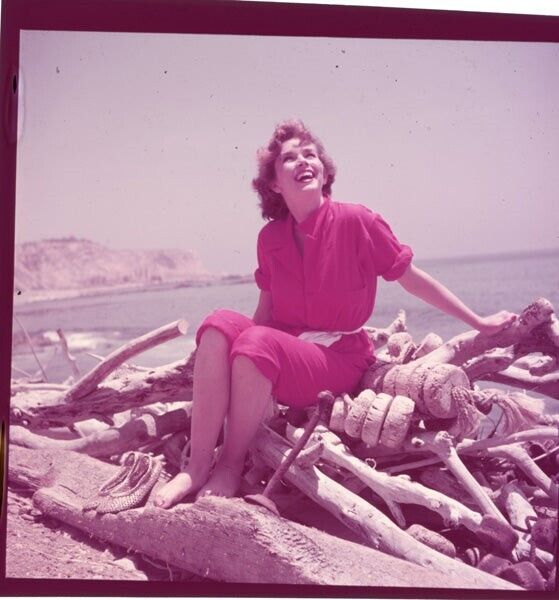

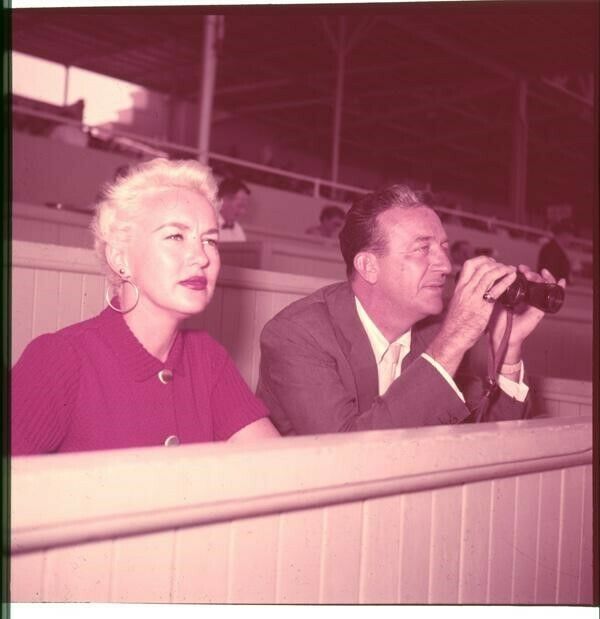

Lovely Pin-Up Bathing Beauty Faith Domergue Original 4x5 Color Film Transparency

$ 3.95

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

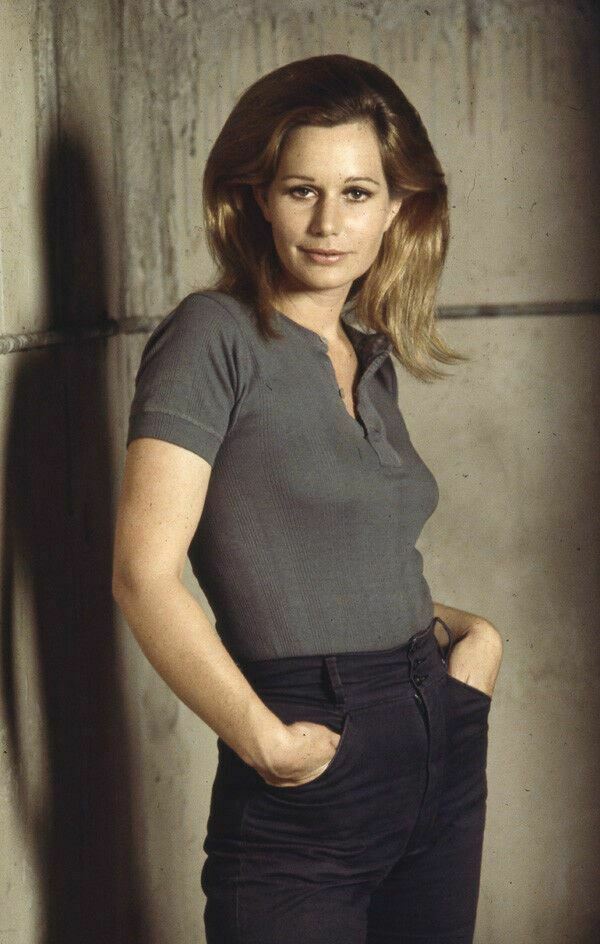

ITEM: This is an original 4x5 Kodachrome Safety Film transparency featuring a color photography portrait by RKO Radio Pictures photographer Ernest A. Bachrach. Dating to the 1950s, this vibrant pin-up portrait features actress Faith Domergue posed in a of white two-piece swimsuit while sunbathing on a vibrant green lawn. This is a beautiful portrait of the star!Despite an early boost from tycoon filmmaker Howard Hughes, alluring brunette actress Faith Domergue never managed to achieve Hollywood stardom. She landed a contract with Warner Brothers while still a high school student. Howard Hughes was struck by the beauty of the young woman and immediately bought out her contract. Eventually, she split from her contract with Hughes, moving on to minor Westerns and anthology drama series before acting in a number of science fiction B-pictures such as "This Island Earth" and "Cult of the Cobra." While not her favorite projects, these movies have gained modest cult followings over the years. In the late '50s, she moved into episodic TV, appearing in a variety of series, including the Westerns "Colt .45" and "Bonanza."

Please note that this auction is for the 4x5 transparency only. There are no copyright or reproduction rights included in the final sale.

Guaranteed to be 100% vintage and original from Grapefruit Moon Gallery.

More about Faith Domergue:

Sultry, brunette Faith Domergue was born in New Orleans, part Creole, but primarily of Irish and English extraction. She was adopted when she was six weeks old. In 1927 her adoptive parents took her to live in California, where she was educated at Catholic schools in Santa Monica. She had her first flirt with the acting profession while still at school, on stage at the Bliss Hayden Theatre. Just after her graduation she suffered a disfiguring injury during a car accident when she was thrown into a windshield, and spent 18 months undergoing intensive plastic surgery. Still in her teens, she was briefly married to Acapulco night club owner and bandleader Teddy Stauffer.

By 1941 she was properly back in circulation. "Discovered" by a Warner Brothers talent scout, she was signed to a contract and her name streamlined a la Hollywood to "Faith Dorn". Sometime at the end of May that year young Faith found herself at a studio party (it was not unheard of for underage ingénues to be thrown together with rich or influential men) given on board the Southern Cross, a yacht owned by billionaire Howard Hughes. Hughes, 21 years her senior, became quickly infatuated with the teenager and bought out her contract from Warner Brothers for ,000, then signed her to the studio he owned, RKO Pictures. He also mollified her adoptive parents by buying them a house, and he paid for Faith to take lessons to perfect her diction and acting. The romantic affair continued on-and-off until mid-1943, and was eventually scuttled by Hughes' various indiscretions with stars Lana Turner, Ava Gardner and Rita Hayworth.

In 1945 Faith reclaimed her original name, Domergue (insisting it be pronounced "Dah-mure") and, by the following year, made her screen debut in Young Widow (1946), a film starring another Hughes find, Jane Russell. Hughes then spent the extravagant--for the time--amount of .2 million on Vendetta (1950), the picture that was to catapult Faith to stardom. Three directors went to work on the project, only to be fired in quick succession: Max Ophüls, Preston Sturges and Stuart Heisler. Faith's lack of theatrical training also proved to be a detriment. The picture was eventually completed by Mel Ferrer, but not released until 1950. When it finally arrived in cinemas, it--like Hughes other fiasco, the Spruce Goose--failed to take off. An earlier effort, the film noir Where Danger Lives (1950), was also released at this time. It starred Domergue in the role as a homicidal femme fatale, opposite Robert Mitchum as the lover she manipulates into taking the blame for her murdering millionaire hubby Claude Rains. In spite of another huge publicity campaign, with Faith featured on the cover of "Look" Magazine and articles in numerous other publications, this film also performed indifferently at the box office and caused Hughes to lose interest in his erstwhile protégé.

During the next few years Faith began to freelance at other studios, appearing in westerns: The Duel at Silver Creek (1952), with Audie Murphy; The Great Sioux Uprising (1953), with Jeff Chandler; and Santa Fe Passage (1955) with John Payne at Republic. In 1955 she starred in the first of a trio of sci-fi/horror outings for which she is chiefly remembered. In This Island Earth (1955), shot in Technicolor at Universal, she played a scientist kidnapped by aliens and, with her colleagues, pressed into service defending their world against interplanetary attack. Helped by a clever script and make-up artist Bud Westmore's ,000 creation of a bug-eyed mutant monster, the film was a huge success and has become a cult favorite. Faith essayed yet another scientist engaged in destroying Ray Harryhausen's giant octopus (six-tentacled, because of the minuscule budget) in It Came from Beneath the Sea (1955). In Cult of the Cobra (1955), Faith replaced Mari Blanchard in the role of the high-priestess of a cobra-worshiping cult who assumes the shape of a serpent in order to kill six GIs who have witnessed a secret ceremony.

Following her separation from Argentine writer/director Hugo Fregonese, Faith made three films in England, most notably as queen of the London underworld in Vernon Sewell's Spin a Dark Web (1956) (aka "Spin a Dark Web"). During the 1960s she concentrated on television and appeared in everything from Bonanza (1959) to Combat! (1962), from Perry Mason (1957) to Bronco (1958). After making several films in Italy (and getting married for a third time, to assistant director and theatrical producer Paolo Cossa in 1966)) , she revisited the horror genre in the cheap but cheerful The House of Seven Corpses (1974), as the emotive star of a horror movie who awakens the deceased after reading from the "Tibetan Book of the Dead".

Faith Domergue never quite made it as a major star, unlike Jane Russell. She did, however, acquire something of a cult following because of her involvement in the seminal This Island Earth (1955), as well as her other science-fiction films from this period. Ironically, Faith later confessed that she never much cared for the genre.

- IMDb Mini Biography By: I.S.Mowis

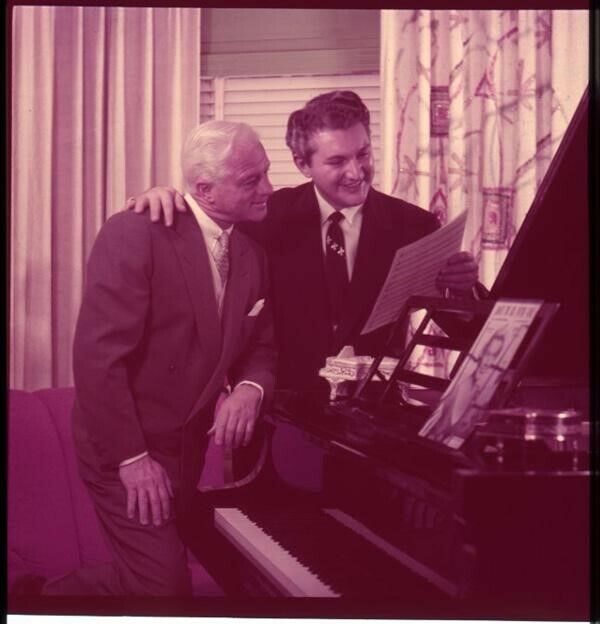

More about Ernest A. Bachrach:

Hollywood’s motion picture still photography defined sophisticated style, shaped personas and created the iconic image of “a movie star” as we know it today. The photographers’ dramatic lighting, dynamic compositions, artful negative retouching and artistic eyes influenced the American public’s perceptions of celebrities and their personalities. Stars were defined as sexy, glamorous, thoughtful, foreboding, all through the scintillating camerawork of these often unsung and forgotten men.

While photographers such as George Hurrell, Ruth Harriet Louise, Clarence Sinclair Bull, Lazslo Willinger and Eugene Robert Richee came to be recognized for their style as well as their artistic sensibilities, RKO’s chief photographer, Ernest Bachrach, gained fame for taking quality portraits that fitted whatever style was requested by art directors or studio publicity chiefs. His discerning eye easily captured the personal essence of the stars he shot, the most important element of a first-rate photographic image. As John Kobal quotes him in his book, “The Art of the Great Hollywood Portrait Photographers,” “Portraiture is very closely akin to cinematography. The cinematographer has very little need for accessories in the making of close-ups; all he needs is a face and some lights and shadows. And that is all the portrait artist needs. Occasionally — but only occasionally — minor props are useful.”

Ernest Bachrach was born Oct. 20, 1899, in New York, and his early years are mostly unknown, though he did sign up for duty in World War I, starting his service at New York’s Ft. Slocum.

By the early 1920s, he was a stillsman for Famous Players-Lasky at their Astoria, N.Y., studio. John Kobal describes how Gloria Swanson came to admire Bachrach’s work as he shot stills for her New York films. Photographer Robert Coburn told him that for Swanson, “There was no other photographer in the world.”

When Swanson formed her own production company in 1926 and returned to Hollywood, she hired Bachrach to shoot portraits and stills for her films, including “Queen Kelly” (1928), “Sadie Thompson,” (1928), and “The Trespasser” (1929). After Swanson’s company folded, RKO put him in charge of their newly created portrait gallery, where he would remain for most of his career.

As David Shields relates in his book, “Still: American Silent Motion Picture Photography,” Bachrach mostly shot stars in full figure before cropping and blowing up images to create head shots, busts, and the like, as did several of his contemporaries like Max Munn Autrey, Ruth Harriet Louise and Jack Freulich. Bachrach focused on capturing expression and thought in his portraits, shaping them to suit whatever a particular medium or outlet required. His images seem alive with possibility as a result. His easygoing, friendly personality and disciplined style endeared him to stars and crew, creating a happy work environment, where his staff called him “Ernie.” His disposition and personality created a loyal, steady work force, including photographers Gaston Longet and Alexander Kahle.

While at RKO, Bachrach shot many of its outstanding stars, including Fred Astaire, Irene Dunne, Ginger Rogers and Katharine Hepburn. He connected particularly with Hepburn, capturing her intelligence, poise and flair in expressive photographs. She comments in Kobal’s book how Bachrach and other stillsmen covered flaws and faults in many women’s faces, creating goddesses out of sometimes ordinary faces.

Bachrach sometimes thought that photographers, along with the studios pushing them to turn out portraits, settled for pretty images that failed to firmly represent a star’s essence or individuality. He described in a 1932 article for American Cinematographer called, “Personality and Pictorialism in Photography,” what he considered quality portraiture: “A primarily pictorial representation of that person’s personality, made by means of photography.”

Bachrach continually sought to improve his craft, shooting independent work to develop his skills in all areas of photography. Hollywood Reporter stated in its May 3, 1933, issue on his innovation of setting portraits on black mounting “unusually artistic.” He received several awards for his outstanding work, including the International Award at the 1933 Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago for “Finest portrait work in the world.” The Artists and Fellows of the Royal Photographic Society awarded him a diploma for his “achievement in exceptional graphic studies” at the Fair.

The artist sought to inform and educate his colleagues and the public in lighting, shooting and composing excellent photographs by writing articles for such magazines as American Cinematographer, International Photographer, Popular Photography and Silver Screen. In the July 1939 edition of Silver Screen, Bachrach noted that the first question a photographer should pose to his sitter was, “To whom are you giving it?” Photographs for parents, love interests, or jobs should all be lit and shot differently. Some of his articles focused on shooting for face shapes and body shapes, as well as technical aspects.

Besides shooting portraits, Bachrach often made time to shoot stills for important or artistic RKO films, such as “King Kong,” “Little Women,” “Sylvia Scarlett,” “Citizen Kane,” “The Secret Fury,” “The Set-Up” and ‘Holiday Affair.”

Bachrach proudly served in various capacities for Local 659, the Cameraman’s Union, serving for years on its Executive Committee and various committees. He helped establish a cameraman’s salon to provide further opportunities in bettering their skills.

Outside of work, Bachrach focused his shooting skills as the leader of RKO’s crack rifle shooting team, composed of members of the photographic staff. The disciplined shooters placed 13th out of 133 teams in the 1936 United States small bore championship series.

Besides painting with light while shooting portraits, Bachrach also dabbled in actual painting, practicing the discipline of composing art true to life with oils and watercolors as well as chemicals, silver, and light.

By the late 1930s and early 1940s, Bachrach sometimes traveled to the East Coast to shoot portraits or stills for films. While traveling, he often visited with magazine art directors and editors to discern their needs for illustrating articles and covers. He also found time to travel to San Francisco “to make portraits of Katharine Cornell and her troupe in Rose Burke,” per the Jan. 22, 1942, Variety.

When Local 659 organized a Stills Show with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in the 1940s, Bachrach often achieved recognition for his outstanding work. The photographer won certificates and first-place awards in 1942 and 1943. In 1947, Bachrach cleaned up at the last stills show, winning two first-place and two second-place awards, and the John Leroy Johnston Trophy for most popular still exhibited in the CBS Columbia Square foyer exhibit: an image of Rhonda Fleming superimposed on a human eye.

Bachrach found solace in work after his wife, Rae, died in 1949, staying busy writing articles, making portraits, and serving his union.

In October 1954, Bachrach retired from RKO after 25 years of work to go freelance and enjoy a little free time. He shot stills for “Around the World in 80 Days” and “Run of the Arrow,” among others.

Ernest Bachrach passed away March 24, 1973, virtually forgotten by the film community. Thanks to the work of photography scholars like John Kobal and Mark Vieira in the 1980s-2000s, his outstanding skills are once again highlighted galleries, articles and books. While not as famous as photographers like George Hurrell, Ruth Harriet Louise, or Clarence Sinclair Bull, Ernest Bachrach ranks as their equal in creating elegant, iconic portraits defining stars’ personas to legions of movie fans around the world.

Biography By: Mary Mallory / Hollywood Heights:

Ernest Bachrach Defines RKO Glamour